By Billy Burton

I can’t remember when or how I first found out about Whistle Down the Wind, Bryan Forbes’ timeless and endearing classic about three Lancashire children who discover a runaway criminal and mistake him for Jesus Christ, but I know that I’ve long been aware of its existence. Growing up in the Ribble Valley, close to the villages in which the film was shot in the early 60s, I’ve always been intrigued by the film’s local importance. But even if I can’t quite recall the circumstances in which I first heard about Whistle Down the Wind, I’m pretty sure I first saw it when I was 11, when my interest in cinema was starting to develop. I’d been a film buff for years, but previously, this love had mainly been focused on the likes of Star Wars and Lord of the Rings. In 2017, I decided that I wanted to expand my knowledge of film history and began seeking out some of the classics. Whistle Down the Wind was understandably one film I was eager to tick off my watchlist.

Upon seeing it, I was struck by how familiar it all seemed. The film’s setting and young cast ensured that it would somewhat reflect my own childhood in the Ribble Valley, but you’d have thought that the lives of Lancashire children in 1961 would be quite different to my upbringing in the 21st century. Despite its era, the film bore a great deal of resemblance to my own experiences of growing up in the shadow of Pendle Hill. This is helped by the relatively unchanged nature of the landscape. Indeed, the barn in which the children first discover the escaped convict played by Alan Bates is still instantly recognisable, as is the village of Downham, close to the farm where the children live.

Place plays a key role in Whistle Down the Wind, with the authentic rural locations providing the perfect backdrop to the film’s story of childhood innocence. Malcolm Arnold’s wonderfully evocative and nostalgic score superbly enhances the magic of the countryside. As an aspiring filmmaker growing up around these very same locations, the film has always resonated strongly with me. I, too, have spent many hours of my youth wandering the same patches of farmland shooting my own short films with friends. Perhaps the only noticeable difference between this rural location (when it comes to the bigger industrial towns seen in the film, it’s a different story) in 1961 and the present day, is the relatively car-free roads, allowing gangs of kids to roam free, unconcerned by the potential dangers of the more congested countryside we see today.

Yet this isn’t just a rose-tinted “good old days” portrait of traditional English country life. The sentimentality regarding what seems like a safer, more carefree existence is balanced out by much more serious undertones. This is a film that opens with a scene of a gamekeeper throwing a bag of kittens into a pond, reflecting the harsh reality of rural life. The dramatic centre of the film is the character of Blakey, a murderer, and the attempts by the police to capture him. From early on, the audience begins to suspect that Blakey is the man hiding in the children’s barn, giving the film a level of rather disturbing dramatic irony. Then, of course, there’s the impact of having the film play out as a religious allegory. The Bible is cleverly mirrored in many of the shots and much of the dialogue, such as one of the children being bullied into denying three times that he saw Jesus. These themes are not taken too seriously and are frequently used in a jokey, self-knowing way: when asked by his followers to tell them a story, ‘Jesus’ picks up a magazine and begins reading about “Ruth Lawrence, air hostess”. Later in the film, Kathy is surprised to find out that Blakey smokes, to which he tells her that he “never used to”.

Even though Whistle Down the Wind has subsequently broken down regional boundaries and become a well-established classic of British cinema in general, the sense of ‘northern-ness’ in the film is unmistakable. The children are initially excited by the prospect of their messiah being visited by “shepherds, wise men” and “the mayor of Burnley”. The distinctly Lancastrian locations, along with the kitchen-sink realism injected by northern screenwriters Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall, allow the film to sit alongside the British New Wave films of the same period. The novel on which the film is based was set in Kent; by changing the location, Waterhouse and Hall gave the story a grittier feel, presenting the stark, bleak landscapes of the God-fearing rural north-west.

This regional association is strengthened by the cast of locals who appear in the film. Despite being produced by industry bigwig Richard Attenborough and starring Disney child star Hayley Mills, as well as classically trained actors Alan Bates and Bernard Lee, it’s the Ribble Valley schoolchildren who arguably make the film what it is. It’s rare to see child actors as good as those in Whistle Down the Wind, often because their lines are written by people more than three or four times their age. Waterhouse and Hall were able to craft a screenplay full of highly believable dialogue, delivered to perfection by the children, all of whom keep their strong local accents. As Charles, Alan Barnes has plenty of hilarious outbursts; hilarious not because of the silliness of a young child saying something written by two men in their thirties, but because they seem like a genuine thing a seven-year-old would say.

As someone with a particular interest in film locations, it’s easy for me to tell you how important Whistle Down the Wind is for the film heritage of my local area. But when I presented a speech on the cinema of northern England for my English GCSE, it was this film that caused the most recognition amongst my classmates. And so you might expect, since they too had grown up around these locations, with some even attending the primary school that provided extras as the ‘disciples’. Perhaps this legendary status is also true of The Railway Children in the Worth Valley, or Swallows and Amazons in the South Lakes, or indeed any film with a particularly timeless connection to its rural setting and community. But there’s certainly something special about Whistle Down the Wind that has allowed it to become such a big deal on this side of the Pennines, even all these years later.

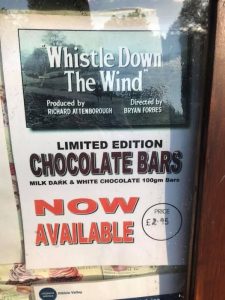

Whistle Down the Wind is undoubtedly a British classic admired by film lovers everywhere. It’s been adapted into an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical (albeit one set in Louisiana, not East Lancashire) and was included in a BFI list of films to see before the age of 14. In an episode of the Empire Film Podcast, directors Edgar Wright and Quentin Tarantino discussed a list made by Martin Scorsese of influential British films, a list that included Whistle Down the Wind. Yet it’s also a film with a personal connection to me and one that, as such, I’ve always thought of as being quite obscure. So it’s quite surreal to hear world-famous filmmakers singing its praises in recent times. It’s clear that this is a film that means a lot to a lot of people, and it’s one I’ll always have a special relationship with.

Billy Burton is a 15-year-old from East Lancashire with a lifelong love of film. Billy enjoys writing (or usually improvising) and shooting short movies with his friends, as well as watching films from a range of different eras, genres and directors.

A keen reviewer, Billy has written a number of pieces which are available to read on Letterboxd:

‘Shallow Grave’ review by Billy B | ‘The Family Way’ review by Billy B

‘Odd Man Out’ review by Billy B | ‘All the President’s Men’ review by Billy B

‘This Is England’ review by Billy B | ‘’71’ review by Billy B

Photo credit: Billy Burton

Bait: A Monochrome Masterpiece

By Stuart Holmes Each year, millions travel across England’s spectacular coastline, from Cleveleys to Cornwall, seeking escapism. We really do like to be beside the

The Boundary-Breaking Beauty of Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey (1961)

By Beth Barker At just 19 years old, Shelagh Delaney wrote her first play – A Taste of Honey (1958). Born to working-class parents in

In the shadow of Pendle Hill: a British classic 60 years on

By Billy Burton I can’t remember when or how I first found out about Whistle Down the Wind, Bryan Forbes’ timeless and endearing classic about